In this series of articles, I am going to be analysis the effects of game-state in football. I am going to consider

- The effect of game state (e.g. the game is tied, 1 goal separates the teams e.t.c) on various metrics (goals, shot ratio, xG e.t.c.)

- How I adjust my metric to reduce the effect of game state for predictive purposes

- What optimal strategies a manager should use to maximise performance

In this first part I am looking at how goal difference is affected by game state.

Introduction

I suspect game state complicates our goal of accurately assessing a team’s performance. We need to comprehend how it influences a team’s performance and the magnitude of said influence.

Let’s think about what the broad influence of a game-state might be:

- When a team leads by a small margin, especially late in the game, they have a reduced incentive to score more goals. They would be happy with the current scoreline as a result. Similarly, when a team trails in a close game, they have an increased incentive to attack. This factor would result in the trailing team attacking/scoring more and the leading team attacking/scoring less.

- A team that leads a will find it easier to attack and score because the opposing team is forced to disregard their defense to turn the game around. This could mean they leave gaps in their defence which can be exploited. This factor would result in the leading team attacking and scoring more while the trailing team attacks and scores less.

- A game that is not close may see reduced intensity. The leading team doesn’t need to score more, and the losing team may be unmotivated with little to no chance of turning the game around.

We mainly want to focus on whether a) or b) plays a more significant role in close football games. Let’s look at some data.

How is goal difference (GD) affected by game state

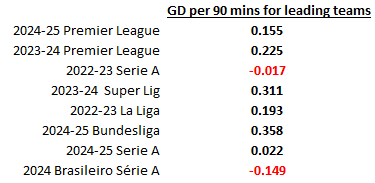

Table 1

When looking across a whole league like this, the goal difference in tied games must be 0. This is because for every goal scored at zero a goal is also conceded at zero. A leading game state is different – a goal scored in a leading state is a goal conceded in a separate (losing) state.

As we can see teams generally improve their GD when they lead.

Does this mean point b) above is a more powerful influence than a). We cannot say that yet, there is a lot more to consider.

Let’s consider a match between 2 specific teams. Team A (of general ability +0.5 GD per game) plays at home against Team B (of general ability -0.4 GD).

While the game is tied, we expect team A to enjoy an average superiority of 1.2 GD per game. (there is a difference of 0.9 GD in ability, and we assume a home advantage of 0.3 GD).

Now we let these teams play each other in a large sample of games. If we observed team A having a +0.7 GD per game during the periods they lead, we can see it’s worse than what their abilities would have predicted so the leading game state is having a negative effect on their performance.

If we adjust for the ability of the teams involved the goal difference of the leading team is 0.5GD per 90 worse than expected. This is our ‘adjusted goal difference’.

How is fixture adjusted goal difference (GD) affected by game state?

I can do a similar measurement for whole league seasons. The expected performance of teams while they lead will be the difference between the average ability of leading teams and trailing teams plus an adjustment for the average extra amount of time a leading team will be at home rather than away.

I can work these things out for the leagues used above. What performance do I expect from teams that are leading?

Table 2

The first column is raw goal difference while teams are leading.

The second column is what the goal difference for leading teams would be if game state had no effect. As you can imagine, it is fairly guaranteed that over a whole season, teams that lead games are on average better teams and also more leading minutes will be at home grounds rather than away.

The third column shows us that leading teams perform worse than would be expected if game states had no effect. It’s interesting there’s 3 premier league seasons in a row where leading teams did not drop their performance – probably just randomness though!

Extra detail

Now let’s look into specific leading states – it may tell us more about why we see this under performance.

Table 3

This shows the underperformance happens in 1 and 2 goal games rather than games that don’t have a close scoreline. Whatever is causing the underperformance is clearly stronger in closer games.

It is also relevant to consider if these differences are more connected to changes in the attack or defence.

If we saw that 1 goal/2 goal games were lower scoring overall, it could imply the leading team was shutting down the game efficiently to preserve their lead. This could help convert a lead into a win and hence isn’t really ‘lower performance’ even if the goal difference per 90 was lower.

Table 4

From this table you can in fact see teams become higher scoring when not in tied states.

We need to consider an adjustment here as football games become higher scoring as full time is approached and leading states are more likely to occur towards the end of the match.

Table 5

The total goals here are a factor relative to the total goals scored between minutes 0 and 10. This table shows the goal scoring rate really in games really increases a lot as the match clock ticks on, even when we only filter for tied game states.

Using this table and the time spent at different game states I can calculate how much higher scoring leading/trailing states should be if the only influence was the idea that leading/trailing states are more common later on in games (as goals have had time to go in).

I calculate factors of 1.14, 1.22 and 1.26 for 1 goal, 2 goal and >3 goal games (i.e. 2 goals games should be 22% higher scoring because 2 goals leads are more likely to be during the latter stages). Using this factor to correct the previous table gives

Table 6

Leading game states don’t look higher scoring anymore, but they also aren’t lower scoring. It’s possible that some teams will be capable of shutting down a game when they lead but it doesn’t appear to be a very common skill. I plan to consider ‘tactical advice’ for teams with respect to game state – I think this topic of total goals will be important. I am finding little evidence that playing more defensively when ahead improves goal difference (in some separate analysis) so I’m thinking it might only be the ‘correct’ tactic if it can shut the game down. More on this in future articles!

What minute of games is underperformance more relevant?

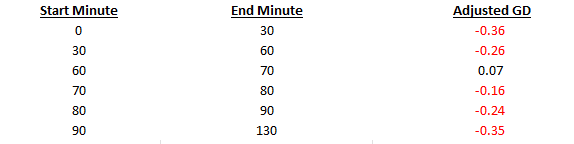

I calculated adjusted goal difference (observed GD in leading states minutes expected goal difference based on team strengths) in leading states for some different time bins for 4 leagues (last 3 PL seasons and 2022-23 Serie A..) and got the following result

Table 7

There is no trend here – it seems like leading teams underperform across every minute.

Goals will often prove hard to work with because they are too random! Ideally I could use a much larger sample here but I don’t have time for everything.

Since I showed table 2 we have learnt that most/all of the underperformance of leading teams is at +1/+2. We have also learnt that the underperformance is probably not strongly related to match minute or as a result of games becoming lower scoring overall.

Conclusion

This underperformance is relevant for modelling football results. The Poisson distribution is one of the most popular ways to calculate the odds for a football game. Goal scoring fits the Poisson distribution fairly well because the mean number of goals expected is approximately equal to the variance of goals scored. It famously underestimates the draw price of games and we’ve just seen why – as soon as teams lead, they start playing worse! This creates a bias for games to return to drawn scorelines.

My current feeling is that this is down to loss aversion. This is a common phenomenon in sports where we observe competitors and teams more motivated to avoid something bad than achieve something great. In golf, professional players make more par putts than birdie putts as the incentive to avoid a bogey appears more powerful than the incentive of achieving a birdie. (https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.101.1.129)

In the case of game states, it may be teams that are losing can dig deeper and find more motivation than teams that are winning. We saw that the effect gets smaller in 2 goal games and especially 3 or more goal games which fits with motivation for the losing team beginning to reduce as they their fate becomes more sealed. Another example in football can be seen with teams that are fighting relegation. It is more common to see teams fearing the drop find more performance than it is to see teams find extra performance when a top 4 finish or title is on the line.

What we have found here today could be an important piece of the puzzle in future analysis!

Next time I will look at how more complex metrics are affected by game state.

Part 2: https://syzygyanalytics.co.uk/2025/07/31/soccer-team-rating-iii-game-states-ii/

Please comment if you have any questions or dm me at https://x.com/SamH112358. Also, you can subscribe to the blog if you wish to get notified about future posts.to play slightly better going forward due to the team regressing to an expected proportion of time in game states that facilitate a better GD.

Leave a comment